This is a report on Ryan Cordell’s presentation during the annual Numapresse seminar that took place a few months ago.

On June 15, Numapresse had the honor of welcoming Ryan Cordell, Associate Professor of English at Northeastern University in Boston (United States). He is a Core Founding Faculty Member at the university’s NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks, which conducts research in both Digital Humanities (DH) and Computational Social Science (CSS). Notably his academic contributions through his role as a Primary Investigator for The Viral Texts Project – a pioneering research project that mainly focuses on Anglophone newspapers and magazines from the 19th century – have provided inspiration for the extensive investigation that Numapresse is currently undertaking, which is why Cordell was invited to deliver a closing lecture during the project’s first annual seminar in Montpellier, France. After multiple sessions during which team members presented their progress, Cordell presented “A Pre-History of Fake News”.

Perhaps contrary to popular belief, the notion of “fake news” is not a recent phenomenon. In fact, Ryan Cordell has been able to trace the distribution of false information back to 19th century newspapers. One of the first media hoaxes that widely circulated was the alleged discovery of extraterrestrials on the moon. The various articles, which were presumably written by Sir John Herschel, were published in New York newspaper The Sun in 1853.

During the 19th century, American newspapers largely consisted of short news stories whose format resembles today’s tweets. According to Cordell “very heterogeneous formats co-existed without any transition: serious news, recipes… and hoaxes”. While the “Great Moon Hoax” printed in The Sun is by now a well-known story, it was not an isolated case. This prompts the following question: how about the stories that were never identified as a hoax? And how should researchers exactly address these texts? Existing tools, Cordell argues, are not sufficient: in order to properly investigate the occurrences of the “fake news” of the past, the use of new methods is key. TextReuse, for example, is a digital tool that enables automatic recognition of identical texts within large corpora – with promising results, that is. So far, Cordell’s The Viral Texts Project, which precisely focuses on these types of questions, has already been able to detect numerous recurrences of identical news stories.

Individual cases are interesting in themselves, but advanced digital tools also allow researchers to demonstrate the specific network exchanges that occurred between newspapers. Additionally, Cordell was able to trace the dissemination of particular news stories across a region or even entire countries.

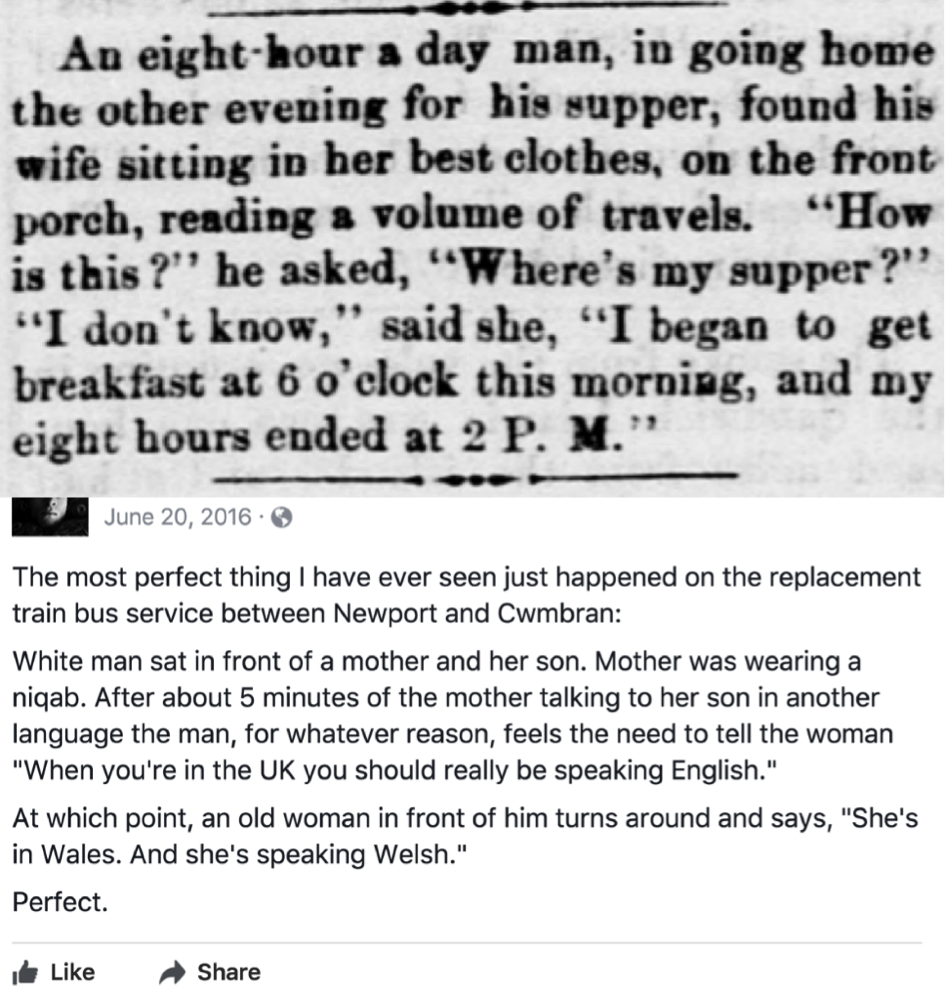

Some formats prove to be particularly suited for the study of viral circulation. Take vignettes, which are unverified and heavily codified anecdotes. In the 19th century (during which the distinction between news and fiction is blurry) they form the ideal hybrid. During his lecture, Cordell stressed the temporality of these vignettes, which, he deems, are timeless in the sense that they can always resurface in accordance with topicalities.

The subject is especially relevant now that fake stories go viral on social media, seemingly on a daily basis. Interestingly, Cordell claims that the structure of 19th century newspapers and their heterogeneous compilations is very similar to what we see online nowadays. New insights from the past might therefore help us to understand the present more clearly.